Columbia University

Irving Medical Center

Neurological Institute

710 West 168th Street, 3rd floor

(212) 305-1818

TaubCONNECT Research Perspective:

October 2023

2: Memory and Language Cognitive Data Harmonization Across the United States and Mexico

3: Education as a Moderator of Help Seeking Behavior in Subjective Cognitive Decline

Rie1 and Sgn1 Form an RNA-Binding Complex that Enforces the Meiotic Entry Cell Fate Decision

|  | |

| Alec Gaspary, PhD | Luke E. Berchowitz, PhD |

To make developmental fate decisions, the cell must sense, accurately process, and in some cases quantify multiple cues. Multicellular organisms rely on cell fate commitment to create the diverse cell types needed for proper development. The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae undergoes a few well-defined cell fate decisions during its life cycle, making it an advantageous model in which to study the mechanisms that commit a cell to a particular fate. Most cell fate decisions, including those of yeast, are understood as being triggered by the activation of master transcription factors. However, mechanisms that enforce cell fates post-transcriptionally have been more difficult to attain. In this study, led by recently minted Genetics PhD Alec Gaspary, we sought to determine whether and how post-transcriptional mechanisms act to affect commitment to meiosis in yeast. Published in the Journal of Cell Biology, the findings of our study are conceptually applicable to all organisms, including humans.

A yeast cell in G1 can remain in G1, continue vegetative growth by budding, transition to filamentous growth, enter sexual conjugation, or to commit to meiosis which occurs in the context of sporulation. The decision of whether to initiate meiosis is crucial to maintaining fitness and, if triggered in error, can be lethal. We performed a forward genetic screen to identify RNA-binding proteins that are required for meiotic initiation. Our screen revealed several candidates, the most severe being a relatively obscure protein called Rie1. We found that Rie1 binds RNA, is physically associated with translating ribosomes, and acts post-transcriptionally to enhance protein levels of the transcription factor IME1 (the master regulatory transcription factor governing entry into meiosis) in response to pro-meiotic cues. We also identified a binding partner of Rie1, Sgn1, which is another RNA-binding protein that supports Rie1 function to promote timely meiotic entry. Our results support the hypothesis that Rie1-Sgn1 is a translational activator that works by recruiting IME1 mRNA to ribosomes.

|

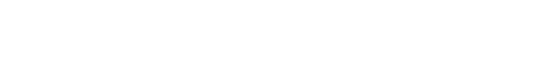

Figure. Rie1 forms a functional complex with the RBP Sgn1. (A and B) Strains harboring N-terminally tagged sfGFP-IME1 and rie1â (B2430, red), wild type RIE1 and SGN1 (B2459, blue), sgn1â (B3375, orange), or rie1â sgn1â (B3378, gray) were induced to sporulate at 30°C. Protein levels of Ime1 and Pgk1 (loading) protein levels were determined by immunoblot and mRNA levels of IME1 and rRNA (loading) were determined by Northern blot. (B) Quantification of Ime1 protein levels corrected for IME1 mRNA levels are shown. Biological replicates = 3. (C) AlphaFold2 output of individual Rie1âSgn1 structures and AlphaFold2 Multimer output of predicted Rie1âSgn1 complex. Rie1 is shown in blue and Sgn1 is shown in orange. A ribbon diagram zoomed in on the predicted Rie1âSgn1 interface is shown on right with key interacting residues on Rie1 highlighted. (D and E) Strains harboring SGN1-FLAG and 3V5 tagged RIE1 (B2668) or rie1 D429A, S433A, and S435A (B3551) were induced to sporulate at 30°C. RIE1-3V5 with untagged wild type SGN1 (no tag control, B3114) was also included. Rie1-3V5 was IPed from meiotic lysate using anti-V5 agarose at the indicated time points. (D) Shown are Sgn1 and Rie1 protein levels by immunoblot in lysate, unbound, and 1% IP and 99% IP samples. (E) Protein levels of Ime1 and Pgk1 (loading) were determined by immunoblot with quantifications shown below.

|

Because expression of Rie1 and Sgn1 is not meiosis specific, our results imply that yeast has evolved a way to control meiotic entry via RNA-binding proteins that are expressed in both mitosis and meiosis. We propose that Rie1-Sgn1 complexes are rate-limiting and act directly to promote meiotic entry as switch-like enforcers while also playing an indirect role to repress spurious meiotic entry. When IME1 transcription bursts in conjunction with Rie1 upregulation, downstream of pro-meiosis cues, the probability that an IME1 mRNA encounters a Rie1-Sgn1 complex will increase as a function of both IME1 mRNA and Rie1-Sgn1 complex abundance. Our model is conceptually similar to the âhungry spliceosomeâ model proposed by (Talkish et al., 2019) which rationalizes why splicing of meiotic genes containing sub-optimal introns is more efficient in starvation (Juneau et al., 2007). In this model, spliceosomes are a limiting resource predominantly recruited to optimal splicing sites on abundant transcripts that generally encode ribosomal proteins. During meiotic entry, transcription of ribosomal protein genes is downregulated, which frees spliceosomes to bind to and splice meiotic mRNAs that contain non-consensus splice sites. Like IME1, mis-translating these meiotic mRNAs could be detrimental. For this reason, the cell has evolved fail-safe mechanisms, including the Rie1-Sgn1 complex and meiotic introns, to restrict translation of meiotic mRNAs to the appropriate developmental context.

Luke E. Berchowitz, PhD

Assistant Professor of Genetics and Development (in the Taub Institute)

leb2210@cumc.columbia.edu

Memory and Language Cognitive Data Harmonization Across the United States and Mexico

|

| Miguel Arce RenterÃa, PhD |

Cross-national neuropsychological research is needed to understand the social, economic, and cultural factors associated with cognitive risk and resilience across global aging populations. Memory and language have been shown to be sensitive to age-related cognitive decline and pathological cognitive aging processes and may be more sensitive to subtle cognitive decline than measures of global cognitive function. However, to accurately compare memory and language functioning cross-nationally, cultural neuropsychological expertise is needed to carefully determine whether our neuropsychological instruments are measuring the cognitive construct equivalently across linguistically and culturally diverse populations. By leveraging two cross-national studies of cognitive aging in the United States and Mexico, we applied a cultural neuropsychological approach to derive and validate harmonized cognitive domain scores for memory and language.

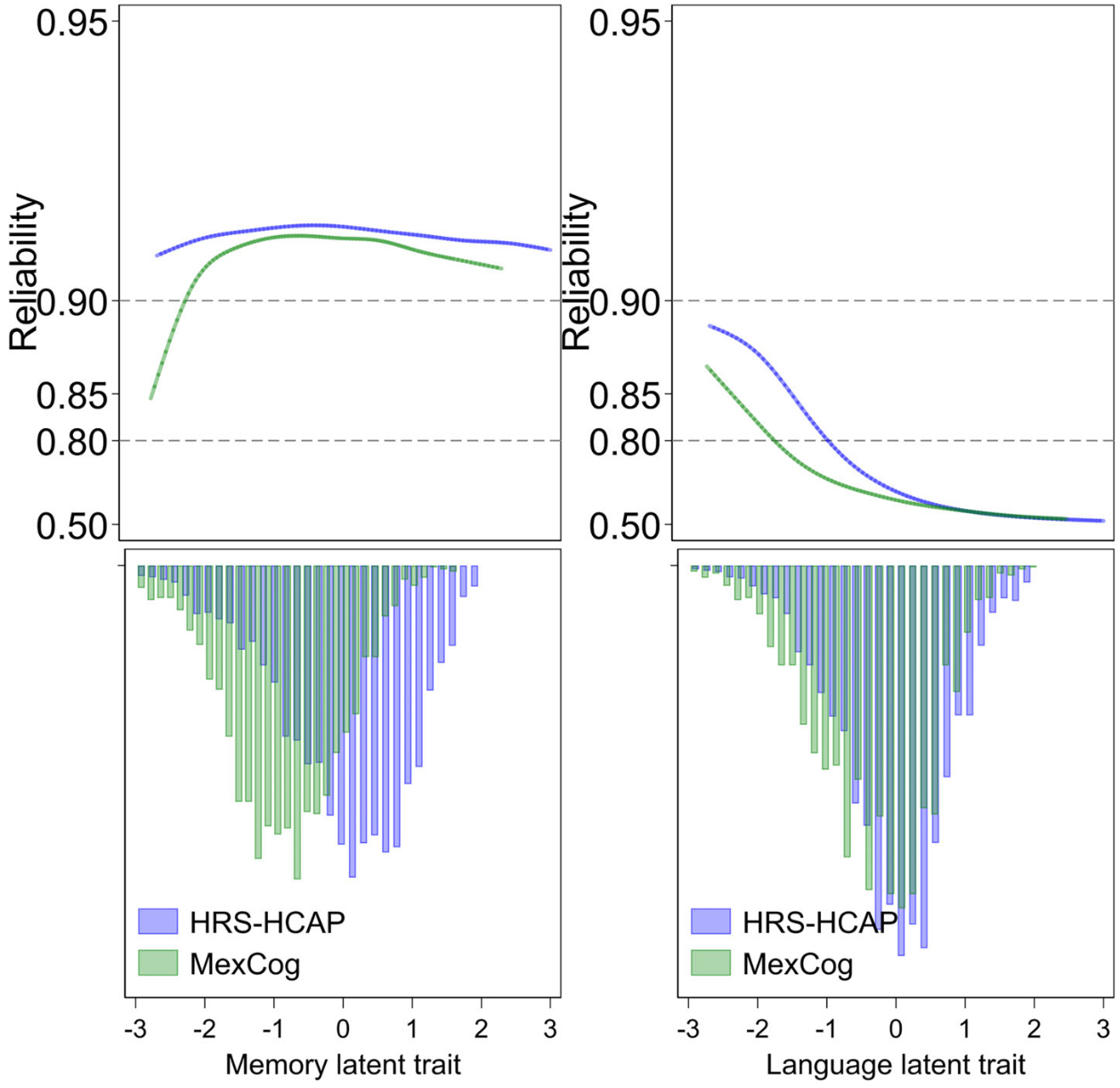

Figure 1. The top halves of the plots represent the reliability of factor scores, and the bottom halves are histograms of factor scores for memory (left panel) and language (right panel) domains by study. The goal of this figure is to illustrate the change in the reliability of estimated factor scores as a function of corresponding levels on the latent trait. HRS-HCAP, Health and Retirement Study Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol; MexCog, Mexican Health and Aging Study Ancillary Study on Cognitive Aging.

As recently reported in Alzheimerâs & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring, data came from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol (HCAP) and the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS) Ancillary Study on Cognitive Aging (Mex-Cog). We used confirmatory factor analysis methodology to create statistically co-calibrated cognitive domains of memory and language. We performed differential item functioning (DIF) analysis to evaluate measurement differences across studies, using a cultural neuropsychological approach to identify comparable items across studies (i.e., cross-study anchors). Briefly, in collaboration with the other neuropsychologist on the team (Dr. Emily Briceño from University of Michigan), we reviewed all memory and language items for cross-study comparability in conjunction with study team members with competence in the languages and cultures represented in the two cohorts. Comparability was evaluated across 1) administration and scoring procedures, 2) coding procedures, and 3) linguistic and cultural equivalence. After review for comparability, potential linking items were classified as either âconfidentâ (i.e., no known features violating item comparability) or as âtentativeâ (i.e., possible features that may violate item comparability) linking items. Items determined to be non-comparable across cohorts were treated as unique items. We then used an item banking approach with confirmatory factor analysis to develop our harmonized cognitive domains and subsequently evaluate for DIF by cohort. Lastly, we then evaluated harmonized scores by examining their relationship to age and education in each study.

|

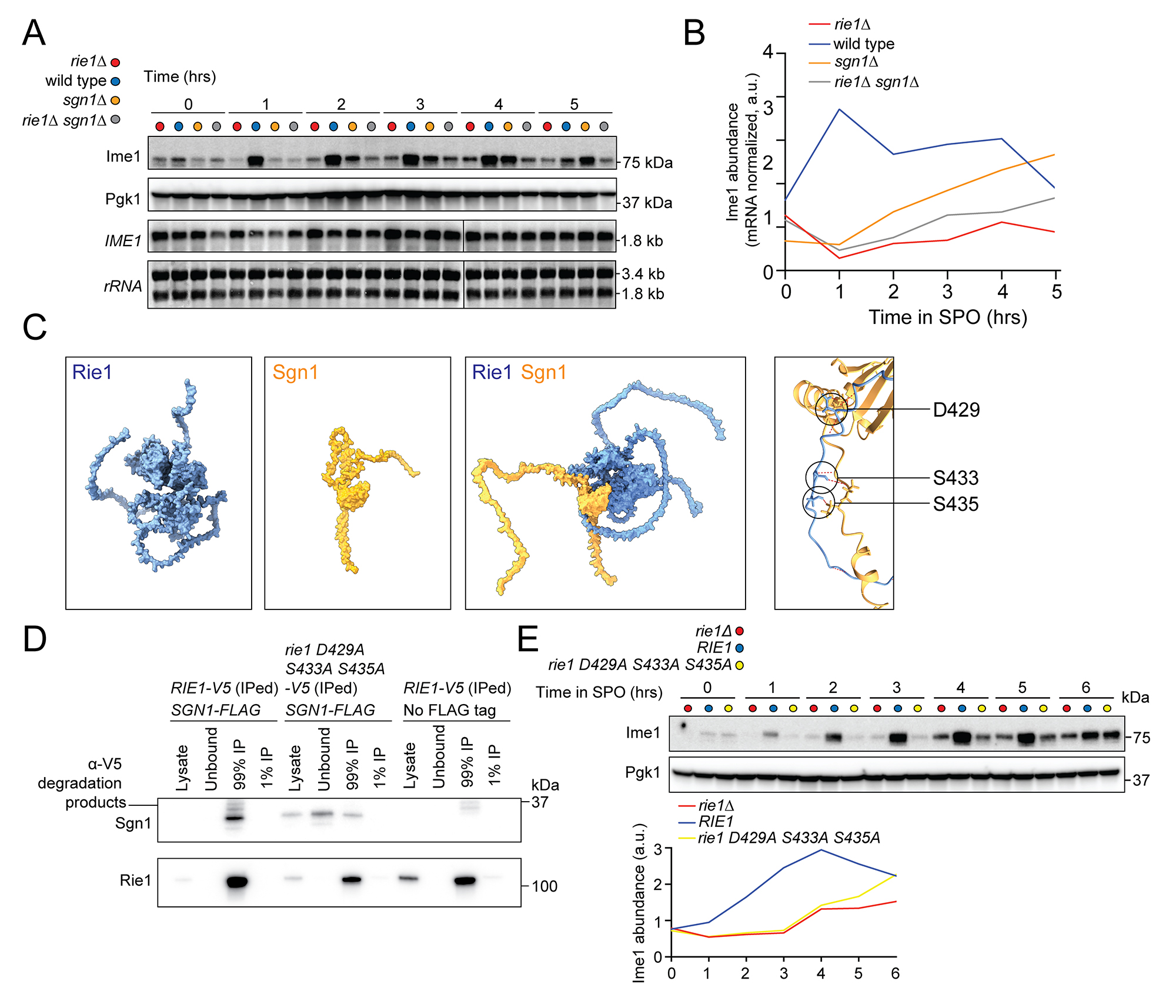

Figure 2. A, Associations between memory factor scores and age, and associations between language factor scores and age by study. B,

Associations between memory factor scores and years of education, and the associations between language factor scores and years of education

by study. HRS-HCAP, Health and Retirement Study Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol; Mex-Cog, Mexican Health and Aging Study

Ancillary Study on Cognitive Aging.

|

After identifying the comparable items to derive our harmonized cognitive scores using our cultural neuropsychological approach, we observed minor measurement differences in the harmonized memory and language scores which impacted few participants in the HRS-HCAP and Mex-Cog, suggesting that cognitive performance is measured comparably in each study by the HCAP (Figure 1). Our results also showed that memory demonstrated strong measurement precision across all levels of the latent ability for both studies. However, the language domain demonstrated lower measurement precision, particularly at higher levels of the latent trait. Initial validation of these harmonized scores demonstrated similar and expected associations with age and education across studies (Figure 2). In conclusion, a cultural neuropsychology approach to statistical harmonization facilitates the generation of harmonized measures of cognitive functioning in cross-national studies. Future work can utilize these harmonized cognitive scores to investigate determinants of late-life cognitive decline and dementia in the US and Mexico.

Miguel Arce RenterÃa, PhD

Assistant Professor of Neuropsychology (in Neurology)

ma3347@cumc.columbia.edu

|

| Stephanie Cosentino, PhD |

Education as a Moderator of Help Seeking Behavior in Subjective Cognitive Decline

Early help-seeking is an important factor contributing to accurate diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer's disease (AD). There are vast and far-reaching disparities in dementia-related help seeking. The decision to seek help for memory difficulties is likely to be multifactorial; it is influenced by a range of factors including knowledge of dementia, family history of dementia, social support, financial resources, perceptions of the healthcare system, and more. These disparities in help seeking will become more critical over time as individuals from marginalized backgrounds including those with fewer years of formal education, a risk factor for dementia, are expected to suffer additional burden with increasing dementia prevalence.

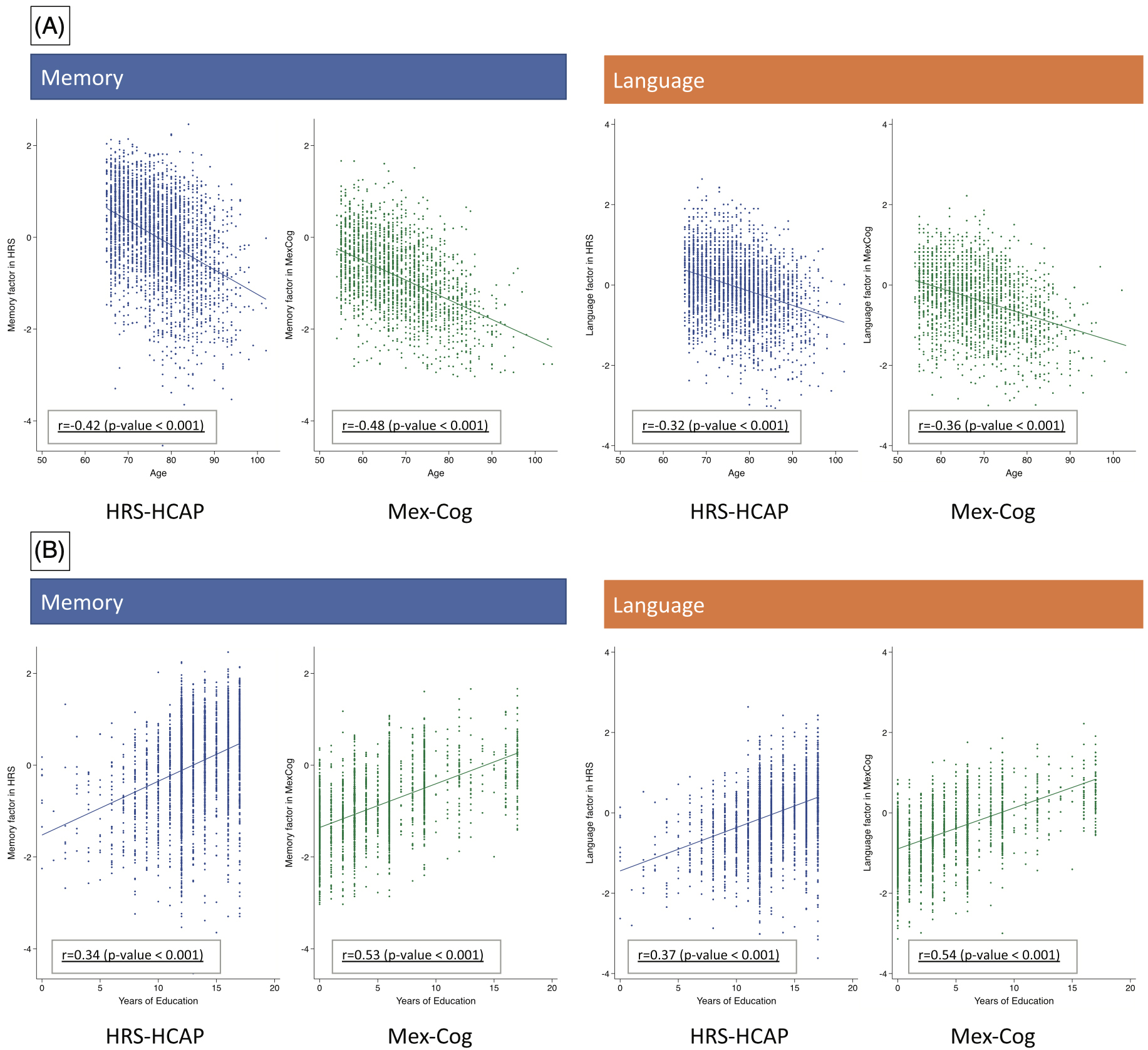

Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD), the self-perception of cognitive decline in the absence of clinical impairment on formal testing, may be one of the earliest clinical indications of AD. We examined the extent to which education, a factor known to influence help seeking across a range of medical conditions, affected the degree to which older adults seek help for subjective cognitive decline. We studied 167 cognitively intact older adults (of which 6% were Hispanic and 22% were Black), with an average age of 73 and median education of 16 years. As recently reported in Alzheimerâs Disease & Associated Disorders, we found that higher levels of SCD and higher levels of education were both associated with greater help seeking for perceived memory changes. Moreover, education interacted with SCD such that in the context of higher SCD, those with higher education were more likely to address memory concerns with a healthcare professional. These findings can be used to inform proactive psychoeducation efforts regarding the importance of memory screenings, memory loss, and addressing memory concerns with healthcare providers.

Stephanie Cosentino, PhD

Professor of Neuropsychology (in Neurology, the Gertrude H. Sergievsky Center, and the Taub Institute)

sc2460@cumc.columbia.edu