Columbia University

Irving Medical Center

Neurological Institute

710 West 168th Street, 3rd floor

(212) 305-1818

TaubCONNECT Research Perspective:

May 2023

2: Effects of Brain Maintenance and Cognitive Reserve on Age-related Decline in Three Cognitive Abilities

3: High School Quality is Associated with Cognition 58 Years Later

4: Older Adults Compensate for Switch, but not Mixing Costs, Relative to Younger Adults on an Intrinsically Cued Task Switching Experiment

Polygenic Risk Score Penetrance & Recurrence Risk in Familial Alzheimer Disease

|  | |

| Min Qiao, PhD | Badri N. Vardarajan, PhD, MS |

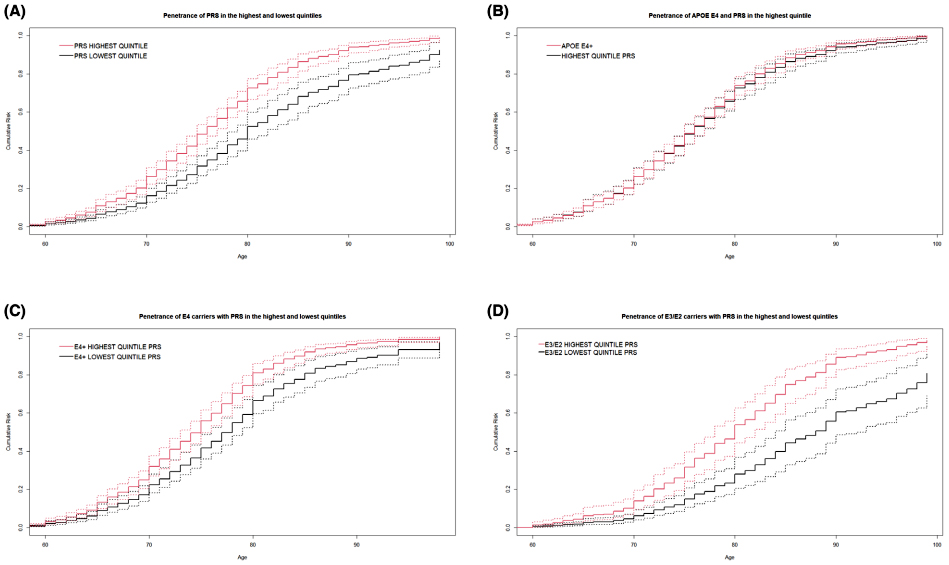

The largest and most recent genome-wide array study (GWAS) of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), co-authored by multiple faculty from Taub, identified over 70 genetic loci associated with late-onset AD, overwhelmingly confirming its polygenic nature. Polygenic risk scores (PRS) are a useful and inexpensive method to determine penetrance and recurrence risk in AD and other diseases. In the current study, together with first author Min Qiao and colleagues from Taub, we aimed to assess the potential clinical utility of PRS in addition to the apolipoprotein ε4 (APOE-ε4) allele. In collaboration with multiple institutions, we computed the PRS from up-to-date GWAS data and contrasted its penetrance and recurrence risk against APOE ε4 allele in the National Institute on Aging Alzheimer's Disease Family-Based Study (NIA-AD FBS) and in a study of familial AD in Caribbean Hispanics.

Figure 2: Age specific cumulative penetrance comparisons between various groups. The solid lines represent the point estimates of penetrance from 1000 iterations and the dotted lines show the 95% confidence intervals. (A) Age-specific cumulative penetrance of highest quintile and lowest quintiles PRS. (B) Age-specific cumulative penetrance in highest quintile PRS versus APOE-ε4 allele. (C) Age specific cumulative penetrance in highest and lowest quintile PRS among APOE-ε4 carriers. (D) Age specific cumulative penetrance of highest quintile and lowest quintile PRS among APOE ε4 non-carriers (APOE ε3 or ε2 carriers).

As recently reported in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology, we found that a PRS above or below a certain threshold allows estimation of penetrance and recurrence risk for family members regardless of their APOE-ε4 carrier status. Specifically, we found the overall penetrance of AD in the highest quintile of the PRS to be identical to the penetrance of the APOE-ε4 alone. Similarly, cumulative lifetime penetrance of disease in the highest PRS quintile (includes high-risk APOE-ε4 carriers and non-carriers) was identical to APOE-ε4 carriers at different ages.

Badri N. Vardarajan, PhD, MS

Assistant Professor of Neurological Science (in Neurology, the Sergievsky Center, and the Taub Institute) at CUMC

bnv2103@cumc.columbia.edu

|  | |

| Yunglin Gazes, PhD | Yaakov Stern, PhD |

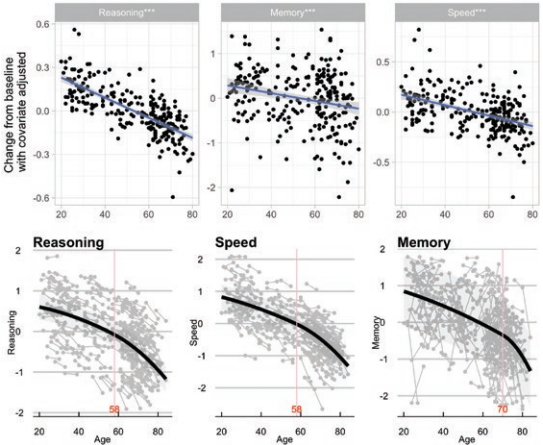

Age-related cognitive changes can be influenced by both brain maintenance (BM), which—as defined in Dr. Yaakov Stern’s recently published consensus framework—refers to the relative absence over time of changes in neural resources or neuropathologic changes, and cognitive reserve (CR), which encompasses brain processes that allow for better-than-expected behavioral performance given the degree of life-course-related brain changes. In the current study, we explored the potential contributions of age, BM, and CR on longitudinal performance changes (two visits, five years apart) in three independent cognitive abilities—episodic memory, reasoning, and processing speed—that capture most of age-related decline. The study followed a group of 254 healthy adults, initially ranging from age 20 to 80 years old, for five years.

Figure 1: (Top) Age moderation on changes in cognitive abilities. For all three abilities, the rate of change decreases with age. All models were adjusted for intelligence quotient, sex, and the two other baseline reference abilities. (Bottom) Performance on each ability at both time points against increasing age. Peak detection and inflection points are shown. Decline in reasoning, speed, and memory were accelerated after the respective inflection points of the quadratic b-spline (vertical lines).

As recently reported in The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, after accounting for age, sex, and baseline performance, we found that, consistent with the concept of BM, individual differences in the preservation of mean diffusivity and cortical thickness were independently associated with relative preservation in the three abilities. After additionally accounting for structural brain changes, we found that, consistent with the concept of CR, higher IQ, but not education, was associated with reduced 5-year decline in Reasoning, and education was associated with reduced decline in Speed. These results demonstrate that both BM and CR can moderate cognitive changes in healthy aging and that the two mechanisms can make differential contributions to preserved cognition.

Yunglin Gazes, PhD

Associate Professor of Neurological Sciences (in Neurology and the Taub Institute) at CUMC

yl2107@cumc.columbia.edu

High School Quality is Associated with Cognition 58 Years Later

|  | |

| Dominika Seblova, PhD | Jennifer J. Manly, PhD |

Education is an important predictor of cognitive performance during the life-course. Few studies have examined the role of educational quality at the time of schooling and include diverse populations; none have measured school quality at a local level. Our aim with this study was to examine the relationship of six indicators of school quality and cognitive performance 58 years after high school. Studying multiple indicators may be important for understanding the best targets for possible policy interventions. Together with former postdoc and first author Dr. Dominika Seblova, we also examined if the studied associations differed by factors that may influence who is positioned to benefit from investments in schools: sex/gender, race and ethnicity, and region of residence at the time of schooling.

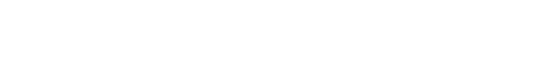

Through a school-based longitudinal cohort—the Project Talent Aging Study—nearly 2,300 participants across 599 schools were assessed by telephone neurocognitive testing. Leveraging this unique cohort, we assessed six indicators of high school quality, reported by principals at the time of schooling, as predictors of respondents’ cognitive function 58 years later. As recently reported in Alzheimer’s & Dementia and on the CUIMC Newsroom, we found that attending schools with a higher number of teachers with graduate training was the clearest predictor of later-life cognition, and school quality mattered especially for language abilities. Overall, our results suggest that increased investment in schools, especially those that serve Black children, could be a powerful strategy to improve later life cognitive health among older adults in the United States.

Jennifer J. Manly, PhD

Professor of Neuropsychology (in Neurology, the Sergievsky Center, and the Taub Institute)

jjm71@cumc.columbia.edu

|  | |

| Teal S. Eich, PhD | Yaakov Stern, PhD |

Aging negatively impacts executive function. One key aspect of executive function is the ability to rapidly and successfully switch between two or more tasks that have different rules or objectives. However, previous work has shown that context impacts the extent of this age-related impairment: while there is relative age-related invariance when participants must rapidly switch back and forth between two simple tasks (often called “switch costs”), age-related differences emerge when the context changes from one in which only one task must be performed to one in which multiple tasks must be performed, even though a trial-level switch is not required (e.g., task repeat trials within dual task blocks, often called “mixing costs”).

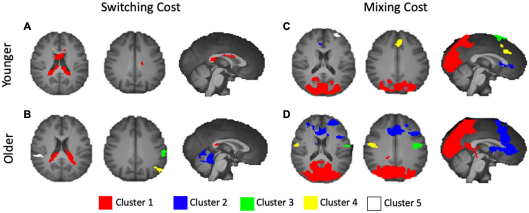

Figure 3. Activations for younger and older adults, separately, for switching and mixing costs. (A) Younger Switching Cost; (B) Older Switching Cost; (C) Younger Mixing Cost; and (D) Older Mixing Cost. Only the five largest clusters for each contrast are rendered. Details of each cluster are shown in Table 1, with colors representing separate clusters according to size: Cluster 1 = Red, Cluster 2 = Blue, Cluster 3 = Green, Cluster 4 = Yellow, Cluster 5 = White.

In the current study, led by former postdoc and first author Dr. Teal Eich (now at USC), in collaboration with Taub faculty Drs. Christian Habeck, Yunglin Gazes and colleagues, we explored these two kinds of costs behaviorally, and also investigated the neural correlates of these effects. Our aim was to provide a clearer understanding of the cognitive and neural mechanisms that underlie task switching performance costs, and the changes that occur to them as a function of age. To this end, we had 71 younger adults and 175 older adults complete a task-switching experiment while undergoing fMRI. We then assessed behavioral performance across the two types of costs—switch costs and mixing costs—and explored the brain areas activated in response to each cost within each age group, and across them.

As recently reported in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, our study replicated previous behavioral findings, with higher age associated with mixing, but not switch costs. Neurally, we found age-related compensatory activations for switch costs in the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex, pars opercularis, superior temporal gyrus, and the posterior and anterior cingulate, but age-related under recruitment for mixing costs in fronto-parietal areas including the supramarginal gyrus and pre and supplemental motor areas. These results suggest an age-based dissociation between executive components that contribute to task switching.

Yaakov Stern, PhD

Florence Irving Professor of Neuropsychology (in Neurology, Psychiatry, the Sergievsky Center, and Taub Institute)

ys11@cumc.columbia.edu