Columbia University

Irving Medical Center

Neurological Institute

710 West 168th Street, 3rd floor

(212) 305-1818

TaubCONNECT Research Perspectives:

March 2021

2: The AD Tau Core Spontaneously Self-Assembles and Recruits Full-Length Tau to Filaments

3: Olfactory Impairment is Related to Tau Pathology and Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease

4: Race/ethnicity and Gender Modify the Association Between Diet and Cognition in U.S. Older Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2014

5: Insights Into the Role of Diet and Dietary Flavanols in Cognitive Aging: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial

Optimizing Subjective Cognitive Decline to Detect Early Cognitive Dysfunction

|  | |

| Silvia Chapman, PhD | Stephanie Cosentino, PhD |

Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD) is the subjective perception that one’s cognition has declined, before such decline is evident on standard diagnostic testing. SCD is believed to precede the Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) stage of AD when, by definition, cognitive deficits are objectively evident. SCD’s potential as a marker of pre-clinical AD was suggested decades ago, but is now receiving renewed attention after a series of studies linking SCD to brain-based AD biomarkers such as amyloid and tau accumulation and brain degeneration. In contrast to such biomarkers, SCD is non-invasive, inexpensive, and easily obtainable. Moreover, while brain biomarkers do not always evolve into clinical dementia (the relevant outcome for the patient), SCD is presumably the beginning of the dementing process. However, in order to determine the true utility of SCD as a harbinger of AD, it is critical to identify better understand the myriad of factors which influence subjective perceptions of cognition.

A new study by Drs. Stephanie Cosentino, first author Silvia Chapman, and colleagues highlights the importance of refining the way in which SCD is assessed when determining its utility as a marker of preclinical AD. As part of an ongoing NIH R01 study, the group prospectively manipulated the way in which SCD was measured (i.e., in general, compared to 5 years ago, or compared to others your age), and how participants were asked to respond (i.e., yes/no versus Likert scale). The group then examined these different SCD scores in relation to a series of novel and sensitive memory tasks. As recently published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, Chapman and colleagues showed that age-anchored SCD (i.e., "Do you have memory difficulties compared to others your age?), when measured on a Likert scale, best approximates individuals' objective performance on the challenging memory measures. These results are in line with the idea that a certain degree of memory decline is expected and experienced with typical aging, and underscore the importance of carefully refining the assessment of SCD to avoid capturing complaints indicative of typical aging. Ongoing work by this group is examining SCD as a predictor of longitudinal cognitive decline as well as in relation to AD biomarkers, and investigating how person-specific factors (e.g., personality, attitudes about aging, metacognition) influence the utility of SCD as a marker of early disease, with the goal of establishing an SCD assessment for older adults in primary care and other clinical settings.

Silvia Chapman, PhD

Postdoctoral Research Scientist (in the Taub Institute and Sergievsky Center)

sc4056@cumc.columbia.edu

Stephanie Cosentino, PhD

Associate Professor of Neuropsychology (in Neurology, the Sergievsky Center and the Taub Institute)

sc2460@cumc.columbia.edu

The AD Tau Core Spontaneously Self-Assembles and Recruits Full-Length Tau to Filaments

Anthony Fitzpatrick, PhD

Anthony Fitzpatrick, PhDTau accumulation is a major pathological hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other tauopathies, but the mechanism(s) of tau aggregation remains unclear. Taking advantage of the identification of tau filament cores by cryoelectron microscopy, Carlomagno and colleagues, including Taub faculty member Dr. Anthony Fitzpatrick, demonstrate in Cell Reports that the AD tau core possesses the intrinsic ability to spontaneously aggregate in the absence of an inducer, with antibodies generated against AD tau core filaments detecting AD tau pathology.

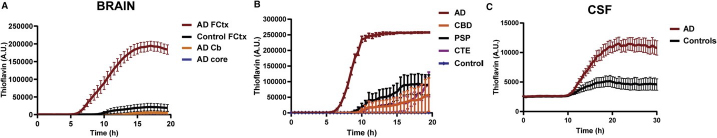

The AD tau core also drives aggregation of full-length wild-type tau, increases seeding potential, and templates abnormal forms of tau present in brain homogenates and antemortem cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from patients with AD in an ultrasensitive real-time quaking-induced conversion (QuIC) assay (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Carlomagno et al. demonstrate the AD tau filament core is able to spontaneously aggregate and recruit full-length wild-type tau to filaments andthat abnormal tau species in brain and CSF from AD patients template the AD core in a real-time QuIC assay.

|

Finally, they show that the filament cores in corticobasal degeneration (CBD) and Pick’s disease (PiD) similarly assemble into filaments under physiological conditions. These results document an approach to modeling tau aggregation and have significant implications for in vivo investigation of tau transmission and biomarker development.

Anthony Fitzpatrick, PhD

Assistant Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics

Anthony.Fitzpatrick@columbia.edu

Olfactory Impairment is Related to Tau Pathology and Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease

|  | |

| Julia Klein (MD Candidate) | William C. Kreisl, MD |

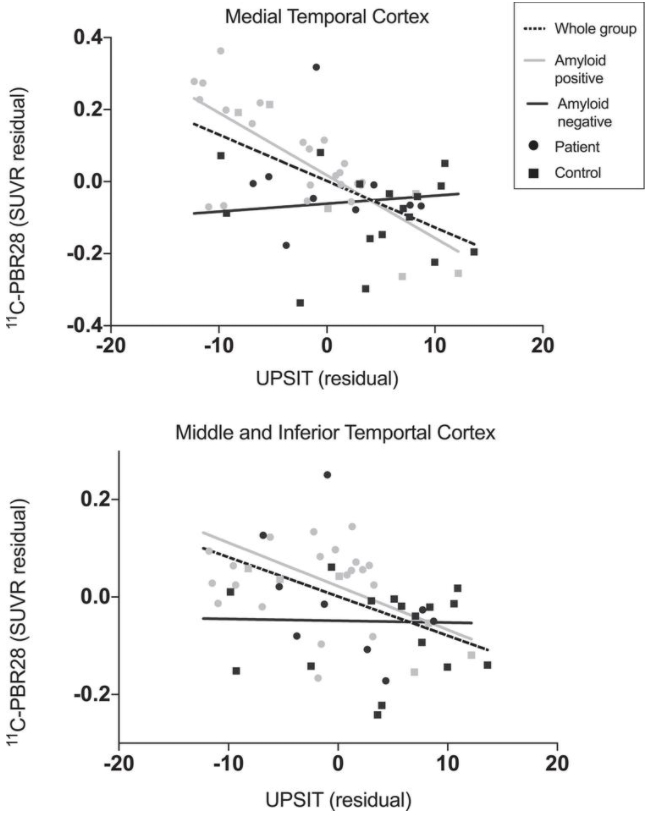

Large community cohort studies by Taub investigators Drs. Richard Mayeux, Davangere Devanand, and others have demonstrated that low University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) scores predict cognitive decline in cognitively normal elders and patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). In addition, several studies, including those by Dr. William C. Kreisl, have investigated the relationships between UPSIT and in vivo measures of AD pathology, particularly amyloid. As further demonstrated by the work of Dr. Kreisl, neuroinflammation is also associated with AD pathology and cognitive decline and can be quantified using PET radioligands, such as 11C-PBR28, that bind the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO), a marker of immune activation. However, to date, no study has evaluated the relationship between odor identification and neuroinflammation.

Figure 1: Relationship between UPSIT score and 11C-PBR28 PET. Lower UPSIT scores were associated with greater 11C-PBR28 binding when all participants were included in medial temporal cortex (r = –0.58, p <  0.01) and combined middle and inferior temporal gyri (r = –0.47, p <  0.01). Correlations remained when only amyloid-positive participants were included (medial temporal cortex: r = –0.74, p <  0.01; combined middle and inferior temporal gyri: r = –0.47, p = 0.02) but not when only amyloid-negative participants were included. Data corrected for age, sex, and TSPO genotype.

Thus, a new study by Dr. Kreisl and colleagues from Taub, including Weill Cornell Medical Student and T35 Summer Research Trainee Julia Klein, sought to determine the relationship between odor identification and neuroinflammation, measured by 11C-PBR28 PET. They further evaluated relationships between odor identification and tau pathology using PET imaging with 18F-MK-6240, a highly specific radioligand for phosphorylated tau, and CSF concentrations of total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau), and the relationship between odor identification and amyloid pathology using CSF concentrations of amyloid-β (Aβ 42).

As recently published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, their findings demonstrate that olfactory identification is negatively associated with progression along the AD clinical continuum, such that amyloid-positive patients had lower UPSIT scores than amyloid-negative controls, and that UPSIT score positively correlated with cognitive performance and hippocampal volume. Klein et al. further found that UPSIT score negatively correlated with PET and CSF measures of tau pathology and neuroinflammation. Taken together, these results suggest that odor identification worsens with AD progression in a manner that may be related to both tau and neuroinflammatory burden.

William C. Kreisl, MD

Boris and Rose Katz Assistant Professor of Neurology (in the Taub Institute)

wck2107@cumc.columbia.edu

Yian Gu, MD, MS, PhD

There is emerging evidence supporting protective roles of certain dietary patterns on cognitive aging and dementia prevention, but it remains unclear whether the association between diet and cognition is similar across different racial/ethnic groups or between women and men. In a new study based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011-2014—a nationally representative sample with men and women participants of multiple racial/ethnic groups—Drs. Yian Gu and Jing Guo, together with collaborator Alanna Moshfegh from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), found that higher adherence to Mediterranean-type Diet (MeDi) was associated with better cognition in older adults aged 60 years and older.

As recently reported in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, they further found that the association between MeDi and cognition was stronger in men than in women and was significant in non-Hispanic Whites but not in other racial/ethnic groups (including non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, and others). Identifying the modification effects by race/ethnicity and gender for the diet-cognition association can help with developing subpopulation-specific preventive measures for cognitive aging.

Yian Gu, MD, MS, PhD

Assistant Professor (in the department of Neurology, Department of Epidemiology, and Taub Institute)

yg2121@cumc.columbia.edu

|  |  | ||

| Richard P. Sloan, PhD | Adam M. Brickman, PhD | Scott Small, MD |

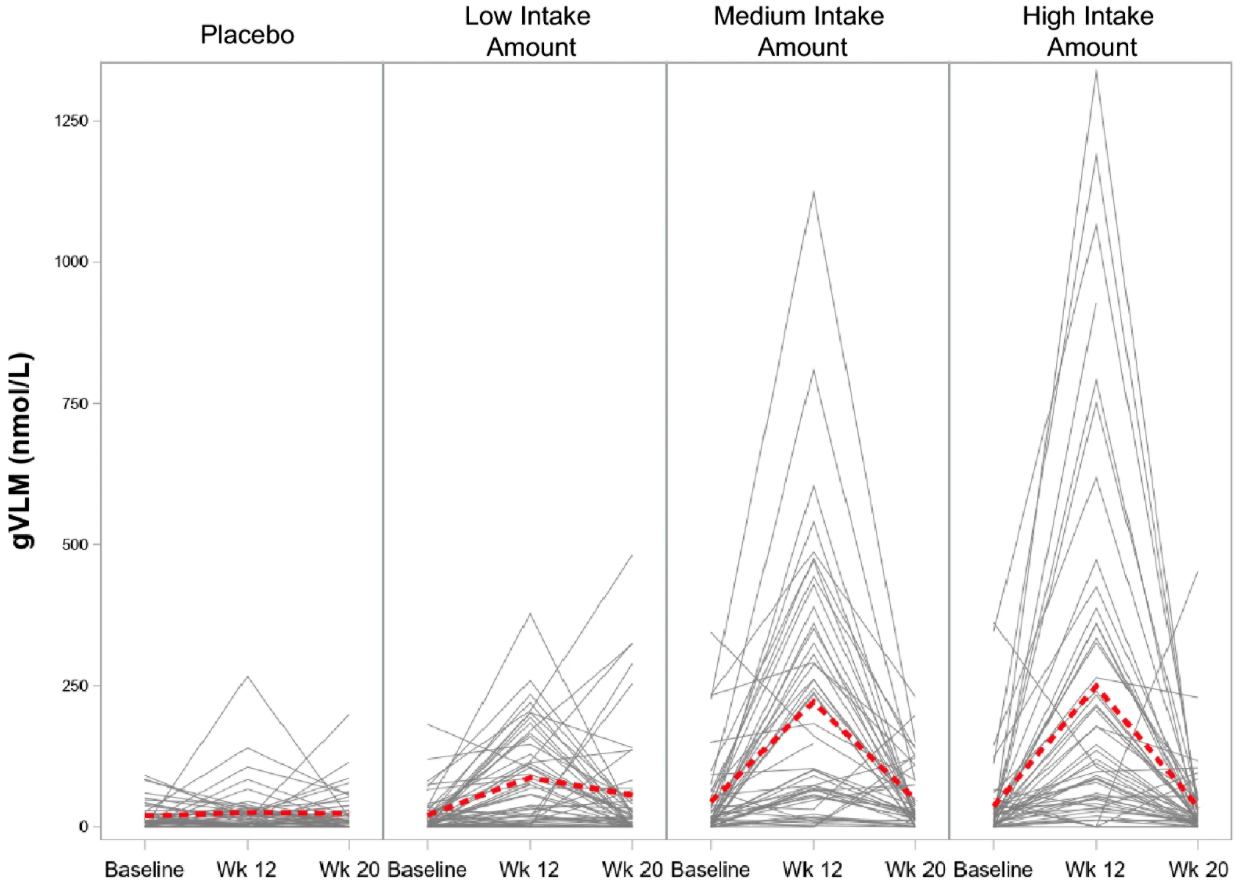

Previous research by Drs. Scott Small, Adam Brickman, and others supports a potential causal link between cognitive aging and functional changes in the dentate gyrus (DG), a hippocampal region vulnerable to aging. In a prior proof-of-concept study, Small and Brickman showed that a smaller-scale flavanol-based dietary intervention resulted in improved performance on "object-recognition" tasks associated with cognitive function localized to the DG. Their latest study, co-led by Drs. Small and Richard Sloan (Psychiatry), aimed to replicate and expand their initial findings through a 20-week placebo-controlled cocoa flavanol-based clinical dietary intervention study in 211 healthy older participants.

The investigators examined a range of flavanol intake amounts and assessed the persistence of effects on cognitive function related to multiple brain regions. As recently reported in Scientific Reports, flavanol intake did not improve performance on the object-recognition task, the study's primary endpoint, failing to replicate previous findings. However, list learning-task performance was improved by the dietary flavanol intervention, again raising the possibility that—at the population level—flavanol-based dietary interventions may have a beneficial impact on cognitive aging.

Figure 3.

Concentration of 5-(3ʹ,4ʹ-dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone metabolites (gVLM) in plasma at baseline, 12 weeks after daily intake of placebo and flavanols at a low (260 mg), medium (510 mg) and high (770 mg) intake level, and at 20 weeks after washout (8 weeks). Data are presented as the individual concentration of gVLM for each volunteer (black lines) and as the mean (red dashed line) over time.

|

Richard P. Sloan, PhD

Nathaniel Wharton Professor of Behavioral Medicine (in Psychiatry) at the Columbia University Medical Center

rps7@cumc.columbia.edu

Adam M. Brickman, PhD

Professor of Neuropsychology in Neurology (in The Taub Institute, The Sergievsky Center)

amb2139@cumc.columbia.edu

Scott Small, MD

Boris and Rose Katz Professor of Neurology (in The Taub Institute, The Sergievsky Center, Radiology and in Psychiatry)

sas68@cumc.columbia.edu